Statement Regarding IP-Theft Incidents

This post addresses the recent infringements incidents by the Chinese company 'Tuopu Mao' (TPM, dba 'Topological Miao' and 'TopMeow & Co') in Mainland China in recent weeks– a company run by ex-employees of Pawprint Press' China-based subsidiary, Pavel Northlake.

UPDATED September 26, 2025: A section added based on findings from the litigation process.

We allege that this company appropriated our designs, materials, and contractors to produce their own products. This allegation is supported by contemporaneous records and third-party confirmations.

Incidents outlined here took place over the course of many months. While we could have commented on them sooner— we felt it best to remain silent. This avoided fanning drama, let us assess the situation, and prepare for proper legal action under China’s strict evidentiary rules governing admissible evidence.

Some interpreted our silence on these matters as condoning TPM’s conduct. We hope this statement clarifies our position.

Since July, we’ve been preparing for litigation. During that time TPM has further infringed the exclusive copyright and trademark rights held by us and our licensor. We are bringing a separate action regarding these infringements, which we also address in this statement.

Preface

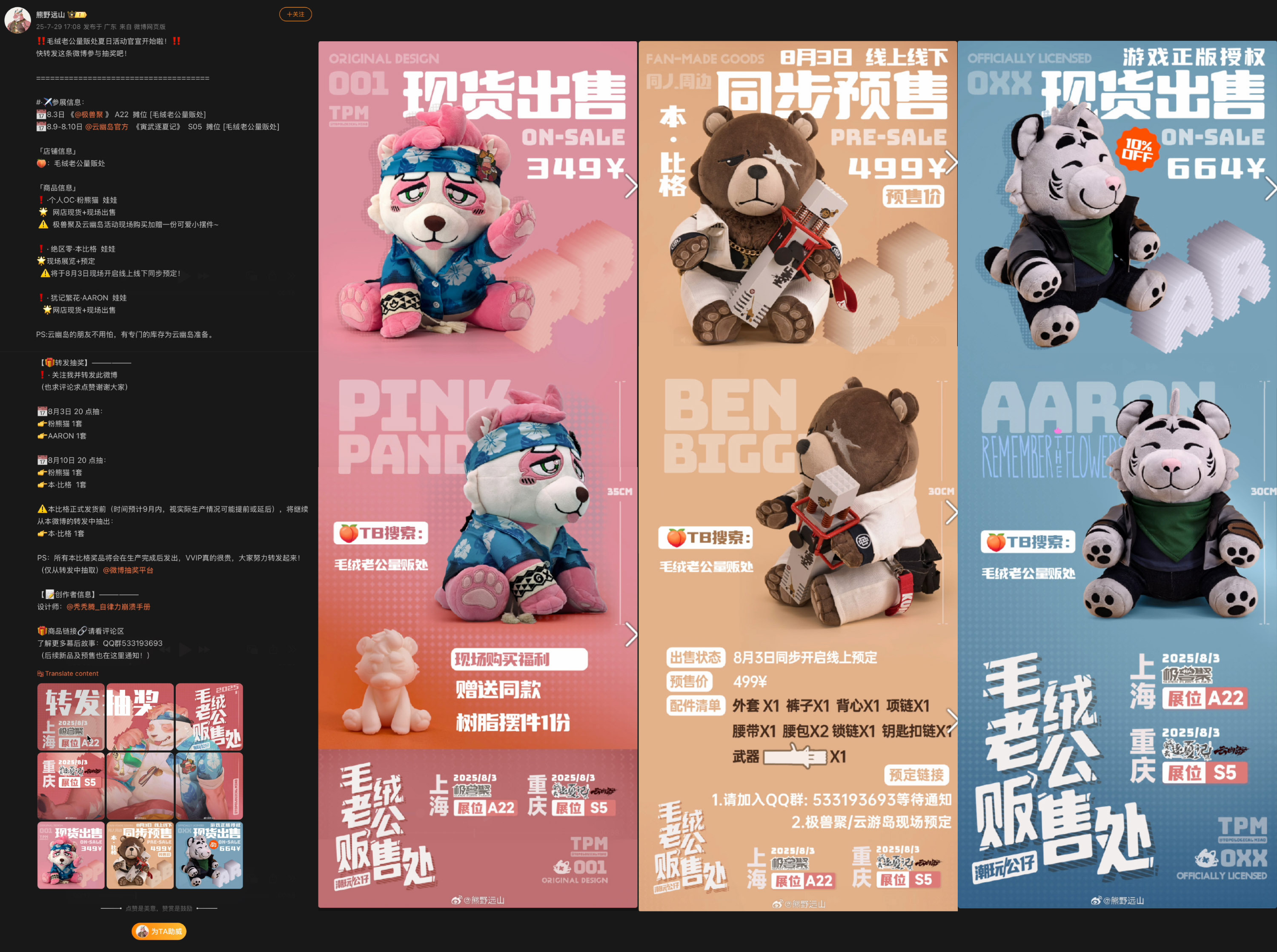

For readers already aware of TPM, we believe the company first came to your attention when it began advertising the Axel Plush. We have since received questions about a Chinese social-media post promoting sales of the Axel Plush (rebranded as ‘Aaron Plush’) at two conventions on August 3 and August 9, published alongside TPM’s announcement of two other plush designs.

We want to make it clear that TPM is not associated with Pawprint Press in any way, and none of its advertising has been approved by Pawprint Press. No TPM personnel previously employed by Pawprint Press or its subsidiaries remain affiliated with, or authorised to represent, Pawprint Press after April 2025.

TPM presented the Axel Plush in their own advertisement without mention of Pawprint Press or the official product name (calling it ‘Aaron Plush’), while utilising the Remember the Flowers logo and the phrase ‘Officially Licensed’. They also placed their own logo and SKU alongside the product, thereby strongly implying that it was TPM’s own product.

This not only violated the copyright of Remember the Flowers, but created confusion among customers who were misled to believe this product was made by TPM and not Pawprint Press. Such confusion-inducing conduct is not only unethical, but also violates the Law Against Unfair Competition of China. (You may read the “TPM Unfair Competition and Deceiving Customers" and “Our Litigation” sections of this statement for details.)

We believe TPM intentionally engaged in fraudulent advertising to trade on the popularity of Axel and Remember the Flowers. This conclusion is corroborated by TPM’s simultaneous promotion of another unlicensed plush based on a character from a well-known game. (Further details of which appear later in this statement.)

Despite the infringements described above, lawful resale of Pawprint Press products is permitted. If you purchased an Axel Plush from TPM, please check whether it includes an orange tag like the image below, and scan the QR code on the tag to verify the product’s authenticity. If your Axel Plush lacks an orange tag, or if the QR code is invalid or already registered, please contact us immediately.

At this time, we cannot verify whether the Axel plushes sold by TPM were lawfully purchased or instead manufactured without authorization. TPM personnel possess sufficient knowledge to replicate this product and, based on evidence in our possession, have used know-how obtained during their prior employment at Pawprint Press. This statement primarily addresses that issue, and we appreciate your patience in reading the remainder.

Background Info

Before It All Began

Many of you know we began preparing for our own factory in summer 2024, and by the end of the year we had successfully established our workspace. While building our in-house capability, we also continued Axel Plush production with the help of several outside contractors.

Two individuals played key roles in that process—and, unfortunately, they are also the central figures in the incidents described in this statement. To minimize personal exposure, we refer to them only as S and W throughout. Those who need to verify related facts may consult the public records referenced elsewhere in this statement.

S had worked with us intermittently since early 2019, contributing to several plush projects as a concept designer and factory liaison. By summer 2024 he was the person we knew and trusted most in the field in China, so we invited him to serve as production engineer for our manufacturing arm. S was also charged with factory liaison during our transition to in-house production.

W and S were a couple, and W had been close friends with several members of our team. W had experience and a good track record in business administration, so we invited him to serve as manager of the new company— we needed someone we knew and trusted (even more) for that role.

Both were offered a six-month prepaid salary—generous by local standards—to help them relocate to Guangdong, plus reimbursement for actual moving costs. This was funded by an external donation to our business. W voluntarily waived the prepaid arrangement and was paid on the regular schedule after the company was established. Both relocated to Guangdong in October 2024, where we had also rented our workspace. Some of you may remember seeing the furnishing process of our workspace documented in our backstage blog.

The first few months were pleasant, at least from our perspective. Axel progressed steadily, and we secured the supply of fillings. Our U.S. team also met with them in Seoul in February on a trip to source some special materials.

Both contributed a great deal to building our manufacturing capacity, and that is a fact we cannot deny. It was shocking, and we felt betrayed when matters ultimately reached their current state.

S Leaving Pawprint Press

In February 2025 S filed for resignation at our company. This event was the cumulation of several incidents behind the scenes.

Several quality-assurance issues occurred in early 2025 on projects overseen by S. The most serious involved a contractor substituting low-grade denim fabric for the specified material, ruining an entire batch of Axel Plush pants. The contractor claimed S had expressly approved the substitution. S neither admitted nor denied this, but any such approval would have been beyond his authority.

The contractor ultimately agreed to partially compensate for our loss, but the incident delayed Axel Plush fulfillment to the United States and significantly increased shipping and labor costs. We were forced to air-freight the pants separately, and our U.S. team spent three days repacking the boxes.

S was not penalized for these incidents; however, we reassigned authority for similar approvals to other team members. We also prohibited him from entering into any agreements or making any commitments on the company’s behalf with third parties. The decision was driven not only by the quality-assurance failures but also by our knowledge that S had accepted gifts and paid meals from contractors. We prohibit staff from accepting any gifts or meals because, in common practice in China, contractors may offer small benefits to client representatives with the expectation of leniency during quality inspections. Even low-value items can create a conflict of interest, which our policy is designed to prevent.

To be clear, we have never alleged that S intentionally traded lower quality standards for small benefits offered by contractors; we make no such claim even now. Our position was simply that S had difficulty refusing others’ requests, as evidenced by his acceptance of gifts and meals from contractors, creating a risk that bad actors could exploit.

S, while acknowledging our concern, maintained that cultivating close personal relationships with contractors, including accepting their “gratitudes”, is necessary for smooth cooperation. That fundamental difference in values precipitated S’s resignation from our perspective at the time. We did not yet know about the later TPM events, and we still do not know whether any plan was already in motion then.

S tendered his resignation in the last week of February, stating that he could not adapt to the company’s management style. We did not object. Frankly, after we removed him from contractor-facing duties, his contributions had been minimal. We also concluded it would be unfair to continue paying him the highest salary on the team while his responsibilities had largely lapsed—especially when our U.S. team had not received regular pay since mid-2024, as we prioritized every available resource toward building our in-house production chain. Our founding members remain off payroll to this day so that every penny goes into production.

Establishment of TPM

The TPM Company, which has the legal name Tuopu Mao (Shenzhen) Toy Company Limited (registration no. 91440300MAEFWF538C), was established on March 26, 2025 — roughly one month after S’ resignation. Public records show seven shareholders including S himself; two others are people we recognize as his friends. The remaining four individuals listed as shareholders are not known to us.

We were unaware of the company’s existence until late April. The short interval between its incorporation and S’ resignation, together with its relatively complex shareholder structure, leads us to suspect the venture was planned prior to his departure.

The registered address of TPM Company is listed as a shared office, which suggests that the company does not maintain its own operational facilities.

How We Discovered TPM

In April, W was caught taking a cloth sample book (of the material later mentioned in a section below) out of the office. Out of curiosity our local person-in-charge asked him about it. W said S was making his own plush (implied to be non-commercial) and wanted to see some material examples. At the time we were unaware of TPM, but had the feeling that S was planning a commercial venture. The following date W was informed that he shouldn’t bring company property to a third party, even if it’s his boyfriend, and especially if they were planning a similar business.

To our surprise, W thought we already knew about TPM from the public records and told us that S had set up a company primarily so he could pay his own social security contributions. (In China, individuals must be on a properly registered employer’s payroll to participate in standard social security programs—most of the cost is borne by the employer.) W insisted that S was merely experimenting with making his own plush and that it was uncertain whether it would become a commercial product.

W further claimed he had absolutely nothing to do with S’ company (at that time we did not know the company’s name and W did not volunteer it). We advised that it would be a violation of company law if he participated in S’ company, given his registered managerial role at Pawprint Press and the trade secrets to which he had access. We explicitly told him we suspected his involvement because, to our knowledge, S lacked the bureaucratic aptitude to handle all the administrative work required to run a commercial enterprise, whereas W appeared to have the necessary knowledge and experience.

W eventually decided to resign from our company, without admitting that he was involved in TPM at the time.

Speculations

The sudden developments made us rethink the logic of what happened over the past few months. S resigned at a very critical moment—right after we had settled all the crucial elements needed to produce a plush: materials, fillings, and the manufacturers we had contracted. Later, we retired most contractors by bringing production in-house, but frankly, with that knowledge one could reproduce a plush to our 2024 standard (for example, Axel) so long as a design diagram is available.

Indeed, TPM was found to be using the very same materials and contractors we had relied on in their own production—precisely the worst-case scenario. Yet, what unfolded went far beyond even our wildest speculation. (As detailed in the next section.)

The reason W chose to stay with us until TPM’s exposure is unknown. Perhaps he was loyal — if so, we appreciate that. But when S left there were still many know-how gaps they hadn’t acquired (for example, the design process of embroidery machine file). W later received related training from our U.S. team, but they didn’t apply that knowledge in their first product. Maybe they didn’t think it mattered at their quality level (the embroidery of their first product later proved to be one of the parts they screwed up most). In any case, there were things someone still working with us could learn. It may sound harsh, but given the unusual circumstances today, no speculation feels too extreme.

TPM Pink Panda Plush

In June 2025, W began advertising a Pink Panda plush based upon his own fursona. We knew this was TPM’s first product but didn’t feel the need to investigate further because we had no reason to believe it violated our rights. However, subsequent developments and newly obtained evidence revealed a very different story.

Company H

During our transition to full in-house production, we progressively internalized each stage, although some processes remained outsourced longer. Among the contractors that continued until June 2025, Company H (full name withheld) handled most of our sewing and stuffing operations. Both S and W were in close contact with Company H by virtue of their roles while employed by Pawprint Press.

We began working with Company H in July 2024, before we committed to establishing our own factory. Company H’s only formal production engagement was the body of the Axel Plush. Additional work had been slated for Company H, but all such plans were canceled after the TPM incident. (A detailed list of the affected projects appears in the “Impact and Future Plans” section.)

Based on information we later obtained, TPM attempted to outsource its first product, Pink Panda, to two toy factories, but neither could complete the work. TPM eventually reached Company H, which at the time already knew that S and W had established their own company and were no longer affiliated with Pawprint Press. (It is worth noting that, after seeing advertisements for Pink Panda, we asked Company H whether S and W had outsourced the project to them; Company H denied this, misrepresenting the facts to profit from both sides.)

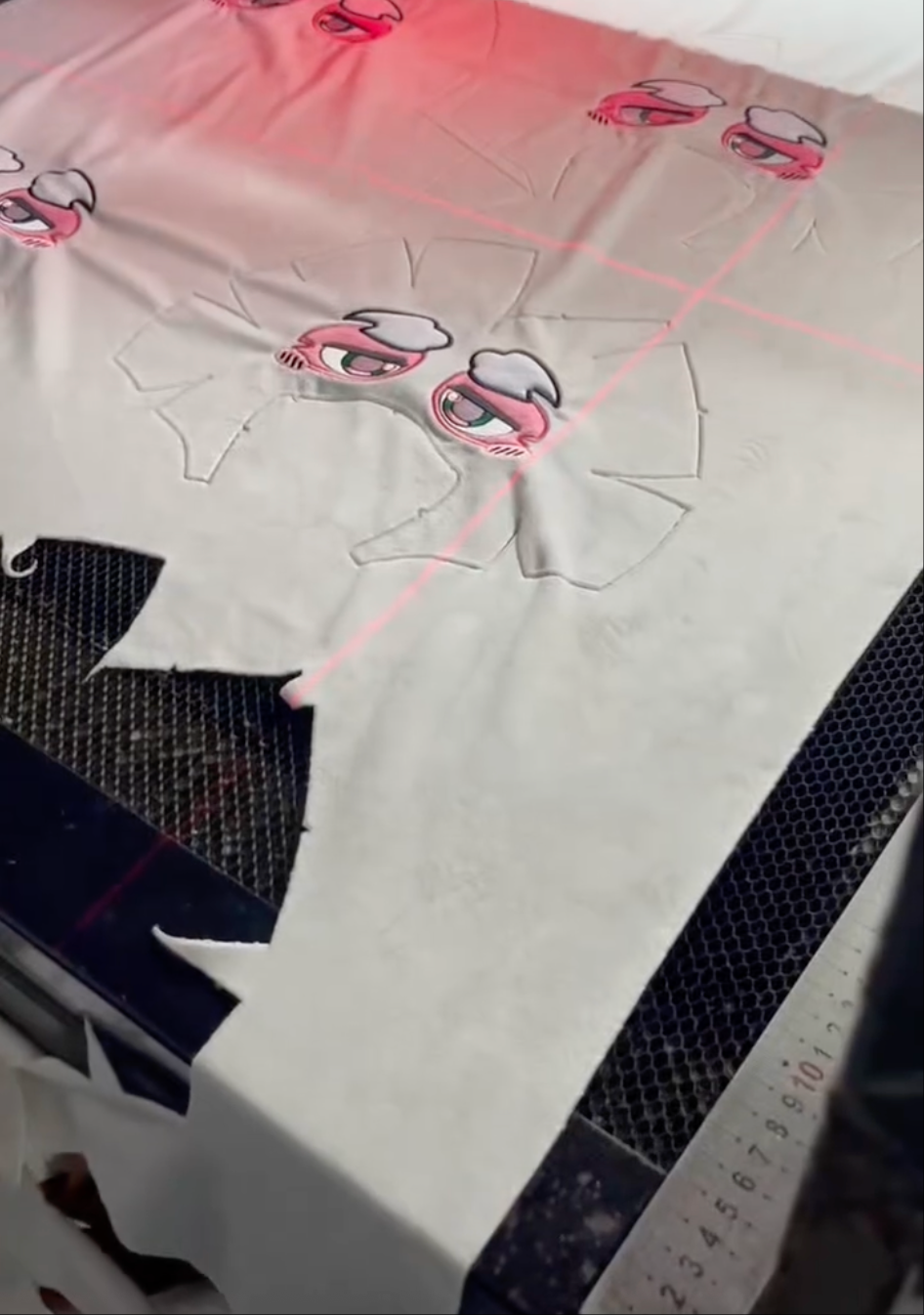

We also allege that Company H deliberately delayed our projects in May and June to give itself time to complete Pink Panda without our knowledge. In June, after becoming suspicious, we made an unannounced visit to Company H’s embroidery subcontractor because Company H had been using the excuse that “our embroidery file is not compatible with their machine.”

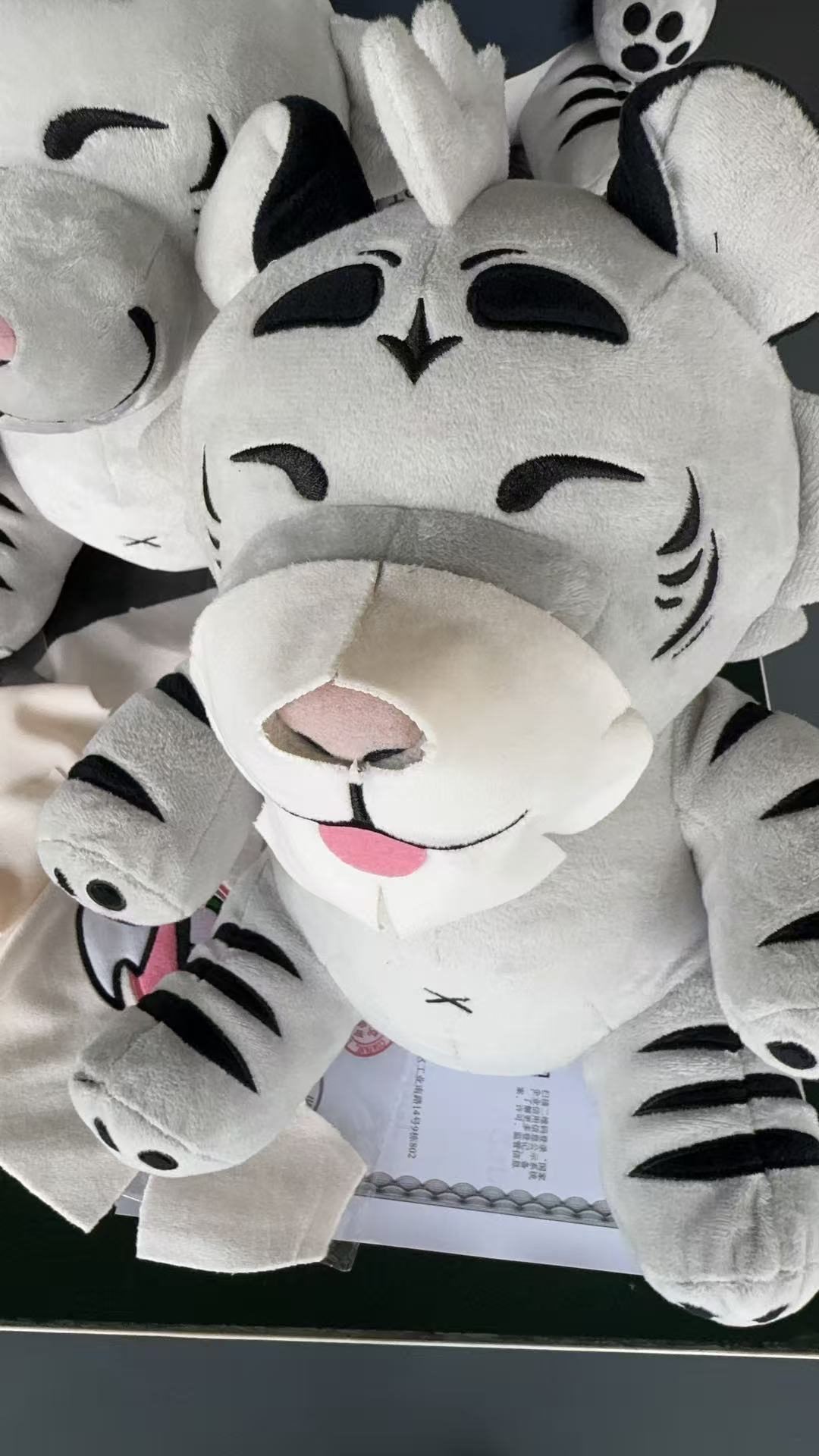

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we discovered the shop actively embroidering Pink Panda components—particularly ironic given that Company H’s manager had told us only hours earlier that they had “never seen” Pink Panda.

Uncovering the Pink Panda Production

After finding Pink Panda at the embroidery shop, we immediately called Company H, and the owner arrived promptly. Embarrassed, they admitted that TPM had tried unsuccessfully to have Pink Panda produced elsewhere. TPM then turned to Company H as a last resort, hoping it could resolve the issues by leveraging the know-how gained from producing the Axel Plush.

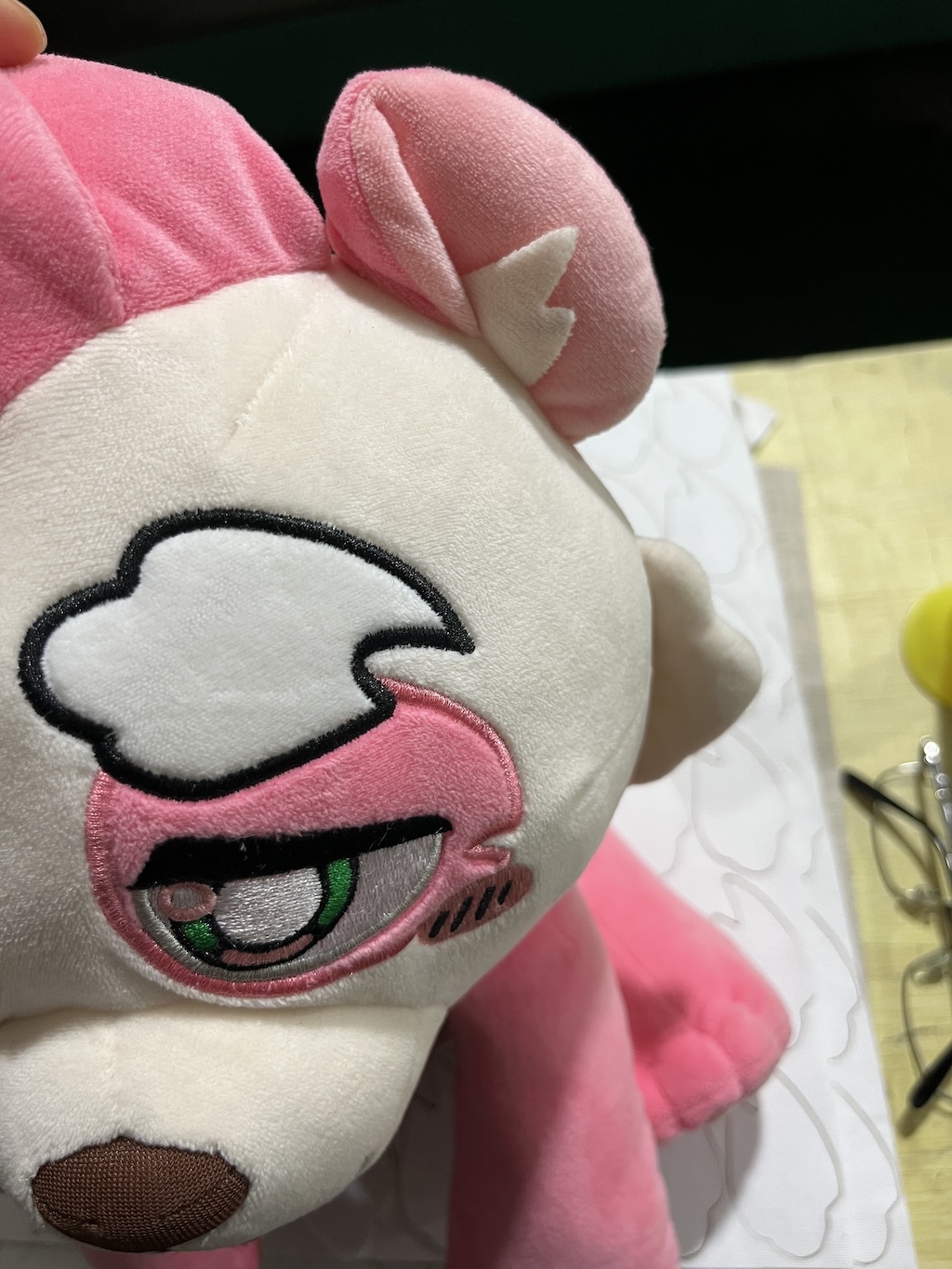

Company H accepted the job at a high price and, apparently, with a much lower quality standard—evident from the embroidery work. It appears they paid the embroidery shop so little that only the lowest-grade paper backing was used, causing severe creasing and buckling around the embroidered areas. The thread used also appears to be of low quality in our opinion.

|  |

|---|

This is particularly ironic given TPM’s claim that it “supervised every step and detail in the production”. In reality, they seem to have handed everything to Company H without even checking how the product was made.

We asked Company H whether they had used any of our design assets in the Pink Panda project, given that TPM engaged them specifically for their experience with the Axel Plush. Company H categorically denied this, stating that TPM supplied its own design diagrams (as we did) and that Company H’s role was limited to assembling the design into production. Company H voluntarily provided us with the design diagrams that TPM had supplied, in an effort to demonstrate its innocence.

However, the initial Pink Panda design diagram that Company H sent us differed from what we observed at the embroidery shop, prompting further investigation. We ultimately uncovered evidence strongly indicating design infringement.

Infringement of Pawprint Design

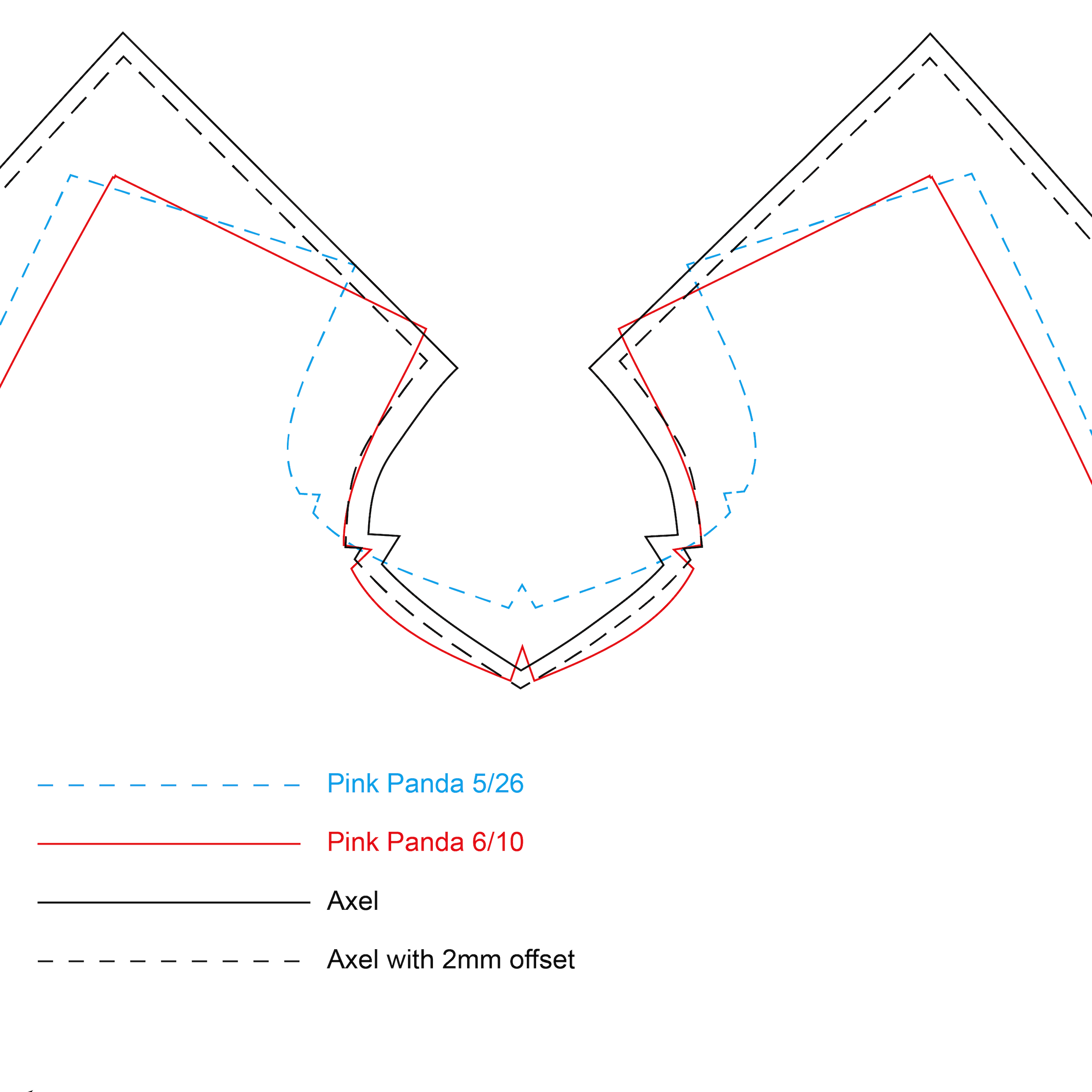

Based on the initial design diagram TPM sent to Company H, dated May 26, it appears TPM created a 3D model of the plush and then attempted to “skin” the model to derive the flat pattern pieces. We were surprised they believed it would be that simple— one would expect at least a basic grasp of topology, especially from a company with “Topology” in its name.

They also cannot reasonably blame the factories they first approached, because the design diagram TPM provided did not form a proper closed contour. We now understand why Company H described TPM’s earlier failures as “they couldn’t close it up.”

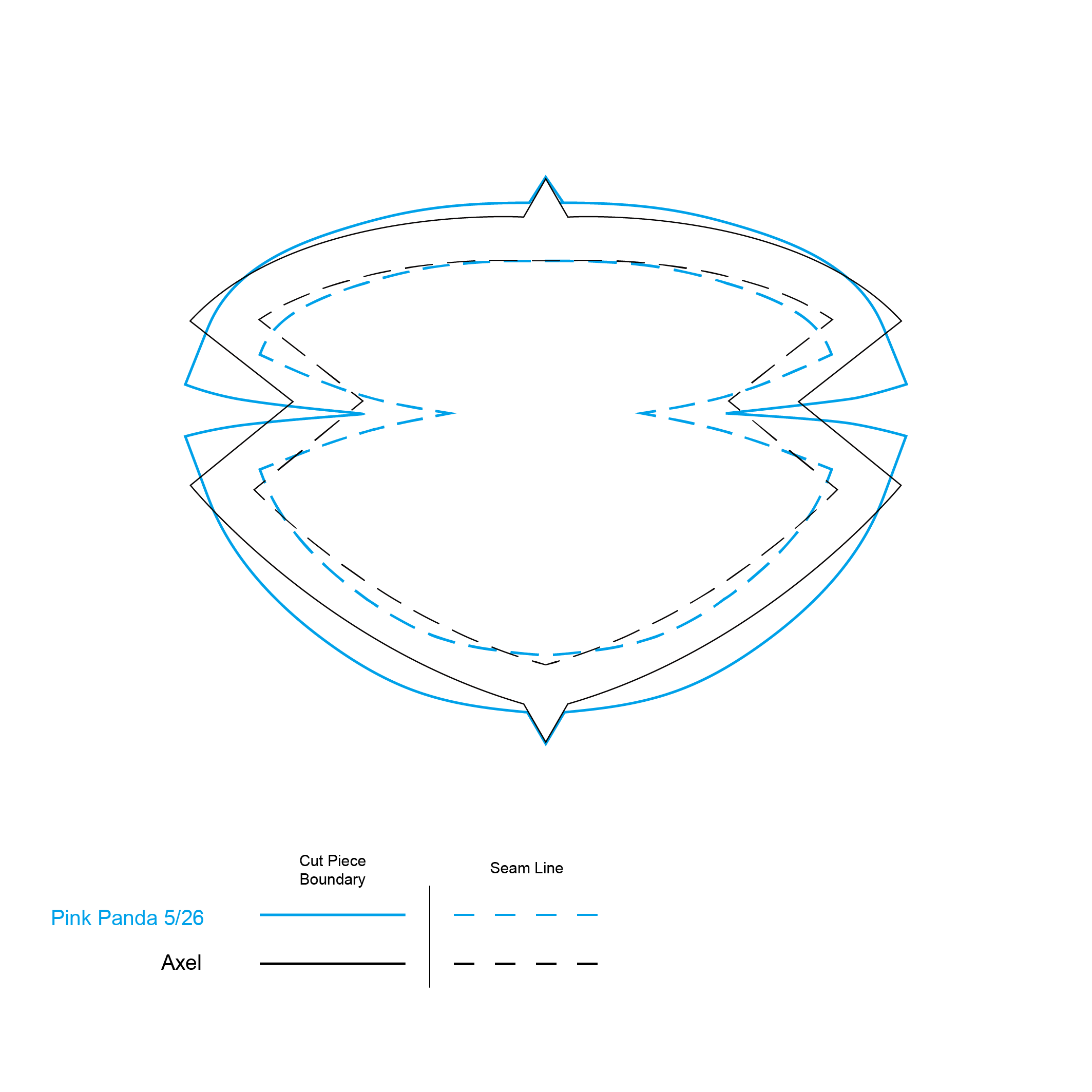

Despite that, the Pink Panda trial sample we saw at the embroidery shop appeared structurally sound—imperfectly made, but without fatal design flaws. We then reviewed the embroidery instruction sheet Company H provided. Because such sheets include outlines of the cut pieces for the embroidered panels (that’s why we never provide contractors with assets beyond their contracted scope), we were able to compare those outlines with TPM’s May 26 design diagram and found material discrepancies.

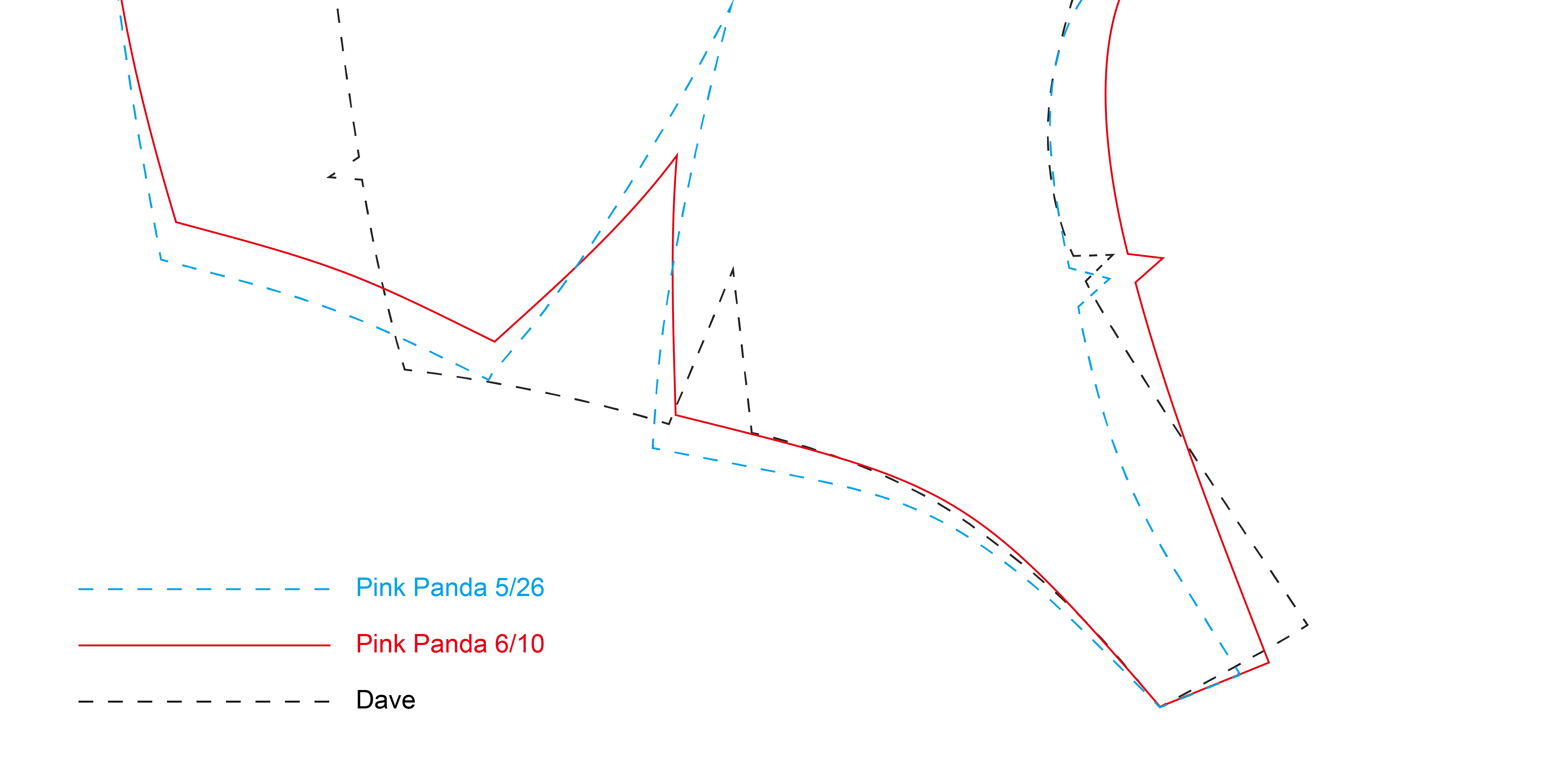

The Pink Panda has embroidery only on the face, muzzle, palms, and soles. Accordingly, the embroidery instruction sheet only contains outlines for the cut pieces of those parts only. Compared with the May 26 design diagram, the muzzle piece is substantially modified. The face piece shows subtler changes, but the key structure near the neck has been adjusted—the very area we anticipated would be most problematic in the May 26 design.

The embroidery instruction sheet is dated June 10, which drew our attention because on June 7 Company H had just received from us a Dave prototype and two complete sets of cut pieces. Our plan at the time was for Company H to finish the body of the Dave Plush.

We then compared Dave’s face piece with Pink Panda’s and found that the key neck structure—previously noted as differing from TPM’s May 26 design—is nearly identical to Dave’s. We call it “nearly identical” only because of a minute variance (see diagram below), which likely reflects a measurement discrepancy given that Company H had only physical cut pieces, not the original digital pattern file.

It is also worth noting that, around the date on the Pink Panda embroidery instruction sheet, Company H asked us for the digital design diagram for Lyall (whose body work we had originally planned to assign to Company H). We refused, as they did not need that asset to perform their scope of work. When we asked why they needed it, Company H said it was to calculate material usage—a rationale that made little sense, since we supply all materials. This request marked the beginning of our suspicions and ultimately led us to discover the Pink Panda production.

Viewed collectively, the previously puzzling events now make sense.

After identifying the first evidence of infringement, we compared Pink Panda against every design to which S, W, and Company H had access. Pink Panda’s heavily modified muzzle piece includes a nose section that matches Axel’s muzzle piece (basically Axel with a 2mm offset)—consistent with our finding that the separate nose piece in May 26 design reassembles Axel’s in both size and shape (if you copy one part, you must copy the adjoining part as well—otherwise “it won’t close”).

|  |

|---|

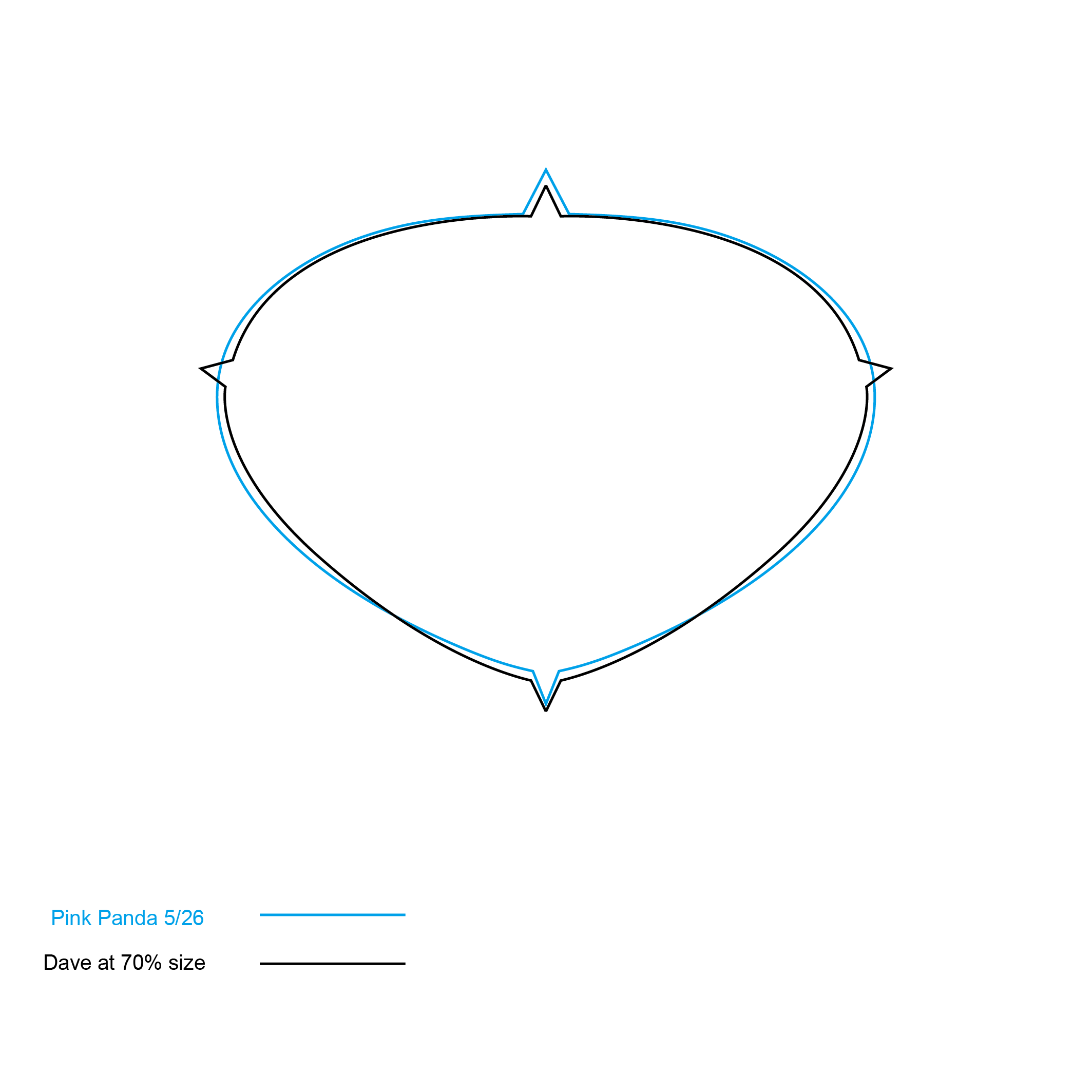

The back lining of the nose also resembles Dave’s, only smaller but exactly 70% of the original size. However, because that geometry is relatively simple and could be coincidental, we leave that assessment to the reader.

We later obtained the Pink Panda cut pieces and performed a simple mock-up; the pieces in question fit Dave and Axel remarkably well in shape.

|  |

|---|

What’s especially interesting is that Pink Panda’s face piece appears to have its positioning markers in exactly the same places as Dave’s. Dave’s facial panel has five markers, and their placement isn’t arbitrary — two of them mark the boundary of Dave’s two-tone muzzle. Pink Panda, by contrast, has a full white muzzle, so it makes little sense for independently designed pieces to share those same marker locations.

Indirect Infringement

Beyond the direct infringement, TPM has exploited know-how and resources gained while employed at Pawprint Press in producing Pink Panda, and potentially additional products. We allege that some of this material qualifies as trade secrets, which the court will determine.

According to evidence we obtained, on June 15 TPM ordered stock fabric for Pink Panda from a supplier we also use. The fabric is from the same product line we selected for Dave, albeit in stock colors. We spent several months testing and validating materials before identifying that line as a strong fit—know-how that, under the latest judicial interpretations of the Supreme People’s Court of China, we contend qualifies as trade-secret information. We are, however, in the process of testing a custom material to replace the material in question.

One could argue that Company H is a trade secret too—which may be true legally—but they clearly didn’t get our real secret: paying 100% attention to every step of production.

There are a few other things on Pink Panda that give us déjà vu: the magnet (Lyall), the enamel badge (Volga), and the scent (Amicus). Of course we don’t claim any rights to the ideas. But seeing all of them packed into one product? Let’s just say it’s lame.

It’s worth noting that while scenting is fairly common, small metal parts—especially magnets—are extremely rare in the plush industry. Most plush toys are intended for children, and including such components is risky. In the Lyall Plush case, the magnet idea came directly from the licensor, who was inspired by a toy his friend had in childhood.

All current Pawprint Press plushes carry an explicit “NOT A TOY” warning on the care label, and Lyall Plush—the only current product with magnets inside the body—also has a clear magnet warning on both the care label and the hangtag.

|  |

|---|

Those warnings are entirely absent on Pink Panda. Technically it’s not our business, but we think it’s extremely irresponsible to fail to disclose an in-body magnet on a product that might be handed to children. A copy is a bad copy if it only copies the gimmick but not the responsibilities that go with it.

The Cover-Up

After their covert Pink Panda production was exposed, Company H promised to cease working with TPM, claiming they “didn’t know” TPM was infringing our designs and would not have accepted the work had they known from the outset. We did not challenge this assertion immediately, partly because our Puff materials were then on deposit with them (as portions of that production were outsourced to Company H) and we needed to secure them, and partly because we wished to observe how they would proceed.

We have a tradition of transparency here at Pawprint Press, not only because we were born honest, but also because we’ve seen too many bad liars. One lie needs another to cover it, and the whole thing eventually blows up. This time, Company H has comically shifted its story in the following order:

-

“They tried two places that couldn’t close it up. We closed it up!”

-

“We didn’t touch the design at all; we just used the cut pieces they provided.”

-

“Everybody copies in this industry. Have you seen Labubu? They copied someone else, too.”

-

“All plushes look similar. Any matching pieces are purely coincidental.”

-

“They signed a confidentiality agreement with us. We can’t say any more.”

Apparently, Company H understands its role in this infringement and has been consulting S and W at the same time. We’re sure of this because we heard some exact same arguments W made when we let him go.

On the other hand, we have to admit that Company H really did want to keep our business. Even at that point, they were still willing to give us a full set of Pink Panda cut pieces. This time they claimed that although they “signed a confidentiality agreement with TPM,” it covered only the digital files, not the physical cut pieces. (Huh?! We’d cancel every project with them on that interpretation alone)

Unsurprisingly, they tried to be clever again. Company H sent us a set of cut pieces, but every infringing piece had been heavily modified so it differed from what was actually used on Pink Panda. Nice try. This provides fresh evidence of their willful conduct.

It should be noted that the face piece Company H provided had all positioning marks removed, making it impossible to tell whether they had aligned the marks to Dave’s muzzle line. The photo above compares the actual Pink Panda face piece with the piece Company H produced: the genuine piece shows clear positioning marks, while the purported piece does not.

(You can also see the creasing and buckling around the embroidered areas, caused by improper embroidery process, as we mentioned above.)

What they didn’t know was that we had already secured the real cut pieces by then. Earlier, we had initiated notarial processes in three different Chinese cities to order Pink Panda as ordinary customers, so as not to alert TPM or give them any chance to swap the product. Most of those plushes are now sealed and archived by notaries public for future litigation, and some were sent to us for analysis.

Aftermath

Knowing Company H was involved in TPM’s infringement was a gut punch. By mid-June, Dave Plush, Lyall Plush, and Puffs were all stuck at stages we’d handed to Company H, and their supposed intentional delays had already eaten up a ton of our time.

This, however, pushed us to accelerate our move to fully in-house production. By August, we had reestablished our production line, with every worker directly under our supervision. No more middlemen—ever. We’ve paid for enough lessons.

The split with Company H was rather smooth. Even in late August they were hoping to keep some of the projects, but we just asked for our Puff materials back. They didn’t push back. A few local subcontractors we know say they haven’t seen Company H work in a while. We don’t know if they’re still making plushes for TPM.

Other than the infringement, the primary harm from this episode was project delays. All projects involving Company H suffered a 5–6-week delay, which we already explained to some affected customers by email. In those emails, we noted that the delay was caused by circumstances we could not disclose at the time due to related legal action. We hope this statement now provides that explanation.

TPM Unfair Competition and Deceiving Customers

Now back to the story we opened with. While we were already stretched thin dealing with TPM’s infringement, they hit us again. In late July, we learned what TPM was doing with the Axel Plush (see the preface section). This is no less serious than the design infringement: their ads, together with related facts, show that TPM has engaged, and continues to engage, in unfair competition and deliberate customer deception for its own benefit.

Fraudulent Advertising

As discussed at the beginning of this post, TPM makes use of the Remember the Flowers logo in their advertisement, alongside the term ‘Officially Licensed’— a deceptive practice that confuses people into miss-attributing our product to them, and miss-attributing permission from the license holder.

In the same promotional materials, TPM also sells an unlicensed plush based on a character from the well-known game Zenless Zone Zero, the details of which are discussed in the following section.

By trading on the reputation of better-known titles and brands, TPM has improperly generated revenue, traffic, and business opportunities. This conduct constitutes unfair competition under the Law Against Unfair Competition of China, as further discussed in the “Our Litigation” section.

False Attribution

In the promotional text TPM published, they list S as the designer of all three plushes—including the Axel (“Aaron”) Plush. This is a false attribution: S did not participate in the design of the Axel Plush.

Although S contributed to some earlier Pawprint Press projects, his design-wise contribution to this product was zero. The plush concept was created by Benny, and the engineering design was produced by our appointed designer, Kenneth. S was not employed by Pawprint Press during Axel Plush’s development; his later involvement was limited to production tasks and did not include any substantive design work.

Therefore, S cannot in any way claim to be the designer of the Axel Plush. TPM intentionally misattributed the credit to S—TPM’s designer and owner—to create the impression that S designed a widely praised product. From that false attribution, TPM could further imply that S designed all Pawprint Press plushes and that such design capability has effectively been transferred to TPM.

The purpose of TPM’s misattribution is to falsely claim design credentials, so that future clients and customers may place confidence in their work. This constitutes a typical form of business fraud and unfair competition. Additionally, the misattribution harms the reputation of the actual designers and those who genuinely contributed to the project.

Concealment and Deception

TPM has concealed its true corporate identity and misrepresented its business affiliation to facilitate knowing infringement of others’ rights and to evade legal liability. They do it primarily to exploit, under false pretenses, good-faith open licenses that rights holders extend to individual creators, while in fact operating as a commercial enterprise.

Along with “Aaron Plush” and Pink Panda, TPM also released a plush based on Ben Bigger, a character from Zenless Zone Zero (“ZZZ”), without authorization from the rights holder, MiHoYo. MiHoYo publicly offers a limited fan-use licence for individuals and non-commercial fan groups who create derivative merchandise in quantities under 300 units, regardless of profit, but this licence is not available to commercial entities. We have also notarized relevant evidence and will be sharing it with MiHoYo’s licensing contact address. If you happen to be a player of ZZZ, you are more than welcome to bring this matter up with their developer team.

Despite this, TPM marketed its Ben Bigger plush as “fan-made,” deliberately misleading consumers. In an online conversation with two inquiring ZZZ fans, S was confronted with the fact that unlicensed merchandise is strictly prohibited. S falsely claimed that “TPM” was just himself and another person, and not a corporation, so that their merchandise would supposedly qualify under MiHoYo’s fan licence. The two fans accepted this explanation. S then asked permission to post the conversation in TPM’s announcement group chat as “proof” that TPM’s operation was legal; the fans agreed only on condition that their names be censored. W later published the conversation screenshot in TPM’s public group chat, where it was retrieved and preserved as our evidence.

The screenshot, together with our English translation, is provided below for reference.

Note

The conversation involves four individuals. The person on the right, who took the screenshot on his device, is a representative of TPM. Based on the context of the conversation, we identify this individual as S.

On the left side are three participants in the group chat, whom we refer to as A, B, and C. A and B appear to be Zenless Zone Zero fans who criticized TPM regarding its unlicensed plush products. C appears to be a random third party and did not substantially participate in the discussion.

We have provided a translation that is as direct as possible, with notes added where necessary to aid reader comprehension. The original Chinese text is preserved without punctuation, which is typical of online conversations in China. Appropriate punctuation marks have been inserted in the translated version for clarity.

|  |

|---|

Footnotes

-

"How did 包老师 (a person unknown, appears to be the user mentioned in the previous message) become friends with this many awesome people?"

-

The term “老米” can be interpreted in different ways in Chinese internet slang. It may refer to MiHoYo, or more generally to "Americans". In this context, we cannot determine whether it was intended to mean MiHoYo, Remember the Flowers, or Pawprint Press.

Knowing and Malicious Conduct

Notably, in the aforementioned exchange, S also claims that the Axel plushes sold by TPM were legally purchased from Pawprint Press, but uses a Chinese designation different from any Chinese name that Pawprint Press had formally used—possibly to muddy attribution and evade liability. He also further asserted that TPM was “officially licensed”.

We also discovered that TPM markets the Axel plush as “Aaron” (for those unfamiliar, “Aaron” is another name for Axel, revealed later in RtF’s story). In the same advertising materials, TPM positioned the plush photograph so as to obscure a portion of the RtF logo.

These “changes” appear calculated to manufacture deniability—i.e., to argue that they did not use the exact names or logos. Although such tactics are too crude to withstand judicial scrutiny, they underscore TPM’ knowledge of infringement and their willful efforts to evade liability.

Our Litigation

Over the past months, we’ve been preparing evidence for legal action, along with the contents of this statement. This is the primary reason why we remained publicly silent on this matter until today.

China’s courts apply a high bar for admissible proof and place a premium on “hard” evidence. Online content—posts, pages, or messages—generally cannot be authenticated at trial by witness testimony or casual screenshots, especially if the content has been altered or deleted by the time of trial.

To be usable in court, such content must be preserved and authenticated by a government-affiliated notary public through a strictly controlled, video-recorded process that captures the full content. The procedure is rigorous, time-consuming, and costly. We intentionally maintained a low profile to allow sufficient time to complete notarial preservation of all necessary evidence, while avoiding alerting the defendants in a way that might prompt the deletion or alteration of key materials.

We are commencing two civil actions against the TPM company and two individuals (“Defendants” in this section).

The First Action

The first action concerning fraud and related misconduct in connection with the Axel Plush product are being filed as of the date of this statement.

You may read a translated version of the complaint below.

COMPLAINT

PLAINTIFF:

[omitted]

DEFENDANTS:

[omitted]

PRAYER FOR RELIEF

- Order both Defendants to immediately remove the infringing content published on the internet.

- Order both Defendants to pay the Plaintiff RMB 1,000,000 in damages for infringement.

- Order both Defendants to reimburse the Plaintiff for reasonable enforcement expenses, including notarization fees, translation fees, courier costs, etc.

- Order Defendant W to issue a public apology on Weibo to the Plaintiff and to the original copyright holder of the work at issue, Jericho, and to keep such apology pinned for no fewer than 60 days.

- Order both Defendants to issue a public apology in the QQ groups they operate to the Plaintiff and to Jericho, and to keep such apology pinned for no fewer than 60 days.

- Order both Defendants to bear all litigation costs of this case.

FACTS AND GROUNDS

The Plaintiff, Pavel Northrake (Dongguan) Toy Company, Ltd. (“Plaintiff”), is a company dedicated to producing high-quality plush toys. It is wholly owned by Project Press Inc., a U.S. company (“Plaintiff’s Parent Company” hereafter, or “Parent Company”).

The Plaintiff’s sole business is to manufacture plush toy products for its Parent Company. Most of these products are designed by the Parent Company under IP and brand licenses it has acquired, and are distributed and sold under the Pawprint Press brand (“PP Brand”). Pawprint Press is a registered trademark of the Parent Company in China.

S, the legal representative of Defendant Tuopu Mao Company (“TPM”), and Defendant W, were both formerly employees of the Plaintiff. They left employment in February and April 2025, respectively, and then founded TPM to produce plush toys similar to those of the Plaintiff.

In July 2025, the Plaintiff discovered that TPM had packaged one of the Plaintiff’s popular products as its own and widely promoted it—including on Defendant W’s personal Weibo account—falsely claiming to have authorization from the IP holder and illegally using relevant trademarks. The Defendants deliberately misled the public into believing TPM had official licensing, causing serious harm and confusion among consumers.

The Plaintiff asserts that the Defendants have infringed its copyright and trademark rights, and their acts of unfair competition have caused both reputational and financial harm. The Defendants must cease their infringing conduct, publicly apologize, and pay compensation. The grounds are as follows:

I. The product and intellectual property at issue

The product in dispute is a plush figure of an anthropomorphic tiger character, officially named Axel Plush. Although it has no Chinese name, suppliers in China colloquially refer to it as “Big Tiger”, which will be used below.

Big Tiger is based on the character Axel from the U.S. video game Remember the Flowers (“RtF”), authored by [redacted] (pen name Jericho, “the Author”). The Parent Company has a long-term agreement with the Author granting exclusive rights to distribute certain merchandise and to use the RtF game logo in defined categories.

The Plaintiff has also been granted exclusive rights from its Parent Company to use the PP Brand within China.

II. Defendants’ false advertising regarding the product

TPM operates under the brand “毛绒老公贩售处“ (lit.“Plush Husband Sales Office”) and sells through a Taobao store and an independent online shop. The Taobao shop is registered under Defendant W, who’s also responsible for its operation. He also operates a Shopify store and promotes TPM products using his personal social media reach. The Defendants also operate QQ groups, where they promote products including the product of this dispute.

On July 29, 2025, Defendant W published numerous promotional posts on his personal Weibo, hyping Topomao’s upcoming appearances at in-person events. Among the materials was a promotional page falsely presenting Big Tiger as a TPM product. This quickly drew the attention of RtF fans and eventually the Plaintiff.

The page displayed photos of Big Tiger but omitted the PP Brand trademark, instead prominently featuring the TPM trademark. It also included the phrase “Officially Licensed Merchandise” in both Chinese and English and displayed the RtF logo.

The page promoted Big Tiger alongside other TPM products in a uniform design and with the same SKU format, thereby strongly implying that Big Tiger was an original TPM product.

Moreover, the Defendants deliberately referred to Big Tiger as Aaron rather than Axel. “Aaron” is the character’s alternative name in the game, only revealed late in the storyline. Official merchandise never uses this name. This choice was clearly intended to evade detection by keyword searches from rights holders.

III. Copyright and trademark infringement by Defendants

The Plaintiff has exclusive rights within China to use the RtF logo. The Plaintiff has confirmed with the Author that the Defendants had no authorization to use the logo.

By using the RtF logo for profit in commercial promotion, the Defendants misled consumers into believing TPM had “official license.” This goes far beyond fair use, violating Article 52 of the Copyright Law and constituting serious infringement.

Further, the Defendants knowingly erased the PP Brand mark from Big Tiger and replaced it with their own, in violation of Article 57 of the Trademark Law.

IV. Unfair competition by Defendants

The Defendants’ core aim was to “ride the popularity” of certain well-known games to draw traffic to TPM, which is a severe form of unfair competition.

Article 7 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law prohibits using packaging or marks of another with certain influence, or otherwise misleading the public into believing there is an association. By displaying the RtF logo and the phrase “Officially Licensed” prominently, the Defendants made ordinary consumers believe they had license from the RtF developer. Under the agreement between the Plaintiff and the Author, only the Plaintiff is entitled to market Big Tiger in China as "Officially Licensed.”

At the same time, TPM also sold pirated plushes of the popular game Zenless Zone Zero, which fans challenged. When confronted, S instead claimed that Big Tiger products they were selling was sourced from “爪印文创” (lit. “Pawprint Creative”) and that TPM had obtained authorization from them. This misled consumers into believing TPM was connected to the PP Brand or even that the Plaintiff had consented to infringement.

In fact, the Parent Company has never used “爪印文创” as a brand name in China. S, as a former employee, knew this well. The use of a fabricated name mirrors the tactic of calling Axel “Aaron” and demonstrates deliberate intent to evade liability.

Defendants fabricated false information to mislead consumers into believing that they were authorized distributors of the Author, and even into believing that “Big Tiger” was an original product of TPM, or that their conduct had at all times been approved by the rights holder of the PP brand. Such conduct constitutes a serious violation of Article 12 of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law, and has caused reputational damage to the Plaintiff, the Author, and the PP brand.

V. Defendants’ willful misconduct and the consequences of their conduct

The Defendants’ infringement was not accidental but carefully premeditated, with deliberate tactics to evade detection.

Defendants knowingly repackaged Big Tiger through false advertising so as to mislead consumers into believing it was a TPM product. Combined with their conduct of deceiving consumers by falsely claiming that TPM’s “Zenless Zone Zero” plush was legitimate product, this demonstrates the Defendants’ willful intent to misappropriate well-known IP for their own profit.

Their Shopify store, which faces foreign consumers, omitted Big Tiger from listings—clearly because they feared faster detection by the Plaintiff or the Author overseas. Their Weibo promotions were timed only days before in-person events to sell products before rights holders could respond.

Remember the Flowers enjoys wide popularity, with merchandise already generating sales of [redacted] RMB for the Plaintiff’s Parent Company, and Big Tiger being the most popular item. Many consumers were deceived into believing TPM held an “official license.” Because evidence-gathering required the Plaintiff and Author to remain silent for nearly two months, this silence was perceived as tacit approval, further amplifying the harm.

Defendants sold Big Tiger at temporarily held in-person events, and it is difficult to verify the exact sales amount. Moreover, due to the Defendants’ prior access to production processes and suppliers, the Plaintiff cannot determine whether the plushes sold were legally purchased or counterfeited, aggravating the uncertainty and risk.

Under the Copyright Law (Art. 54), Trademark Law (Art. 63), and Law Against Unfair Competition (Art. 22), when actual damages or illicit profits cannot be determined, the court may award statutory damages up to RMB 5,000,000. Considering the Defendants’ malicious intent, the popularity of the product, the likelihood of high profits, and the extent of harm caused, the Plaintiff reasonably claims total damage of RMB 1,000,000.

In conclusion, the Defendants’ infringing conduct is malicious in nature and has caused significant harm, and they should bear the corresponding legal liability. The Plaintiff has sufficient factual and legal grounds to bring this action and respectfully requests that the Court rule in accordance with the Plaintiff’s claims.

Respectfully submitted,

To: Shenzhen Bao’an District People’s Court

Plaintiff:

Pawel Northlake (Dongguan) Toy Company, Ltd.

The Second Action

The second action concerning the “Pink Panda” matter—is still in preparation due to its greater complexity and the involvement of a third-party manufacturer.

Legal Basis

The unauthorised use of the RtF logo infringes the copyright owner’s exclusive rights, and therefore violates the Copyright Law of China:

Article 52

Anyone who commits any of the following infringing acts shall, depending on the circumstances, bear civil liability such as ceasing the infringement, eliminating the effects of the act, making an apology or paying compensation for loss:

…

Article 53

Anyone who commits any of the following infringing acts shall, depending on the circumstances, bear civil liability prescribed in Article 52 of this Law; where public rights and interests are concurrently impaired by the infringement, the competent department of copyright shall order the infringer to stop infringement, give him a warning, confiscate his unlawful gains, and confiscate and harmlessly destroy the infringing copies and the materials, tools and instruments mainly used to produce the infringing copies, and may, where the illegal turnover exceeds 50,000 yuan, concurrently impose a fine of not less than one time but not more than five times the illegal turnover; where there is no illegal turnover or the illegal turnover is difficult to calculate or is less than 50,000 yuan, a fine of not more than 250,000 yuan may be imposed concurrently; where a crime is constituted, criminal liability shall be investigated in accordance with the law:

(1) without permission of the copyright owner, reproducing, distributing, performing, projecting, broadcasting, compiling a work or disseminating a work to the public through information network, unless otherwise provided in this Law;

…

Regarding the Pink Panda case, the unauthorized use of our design diagrams also falls within the scope of the same Law:

Article 3

For purposes of this Law, the term “works” means intellectual achievements in the fields of literature, art and science, which are original and can be expressed in a certain form, including:

…

(7) graphic works such as drawings of engineering designs, product designs, maps and sketches, and model works;

…

Article 10

Copyright includes the following personal rights and property rights:

…

(14) the right of adaptation, that is, the right to modify a work to create a new one with originality;

…

Defendants also engaged in unfair competition by “riding the popularity” of the well-known games to divert traffic to TPM Company. They used the RtF logo and “officially licensed” wording in promotions, falsely suggesting their affiliation with RtF. This conduct is likely to cause consumer confusion as to the source of goods or a specific connection with the right holders and constitutes misleading commercial publicity, violating the Law Against Unfair Competition of China:

Article 6

A business entity shall not commit any of the following acts which create confusion, misleading consumers into believing that its own goods is the goods of another business entity or has a certain connection with another entity:

(1) Using, without authorization, any mark identical or similar to the name, packaging or decoration, etc. of another business entity’s goods which has certain reputation;

…

(4) Any other confusing act sufficient to mislead the consumers into believing that its goods of another business entity or has certain connection with another business entity.

Further, Defendants intentionally removed the PAWPRINT PRESS word mark and the “Claw of Quill Pens” logo—both registered in China—from product images and promotional materials, and substituted with TPM’s trademark. This conduct infringes the exclusive rights in the registered trademarks and violates the Trademark Law of China:

Article 57

Any of the following conducts shall constitute an infringement of the exclusive right to use a registered trademark:

…

(5) Altering the trademark registrant’s registered trademark without authorization of the same and selling goods bearing such altered trademark.

…

Impacts and Future Plans

These dramatic incidents caused significant damage to our operations and production; the products listed below were each delayed by at least five weeks:

- Dave Plush

- Lyall Plush

- Puffs

- Dakimakura Pillow Insert

Positive Outcomes

Although we’ve been planning this for some time, these incidents have pushed us towards a more independent production pipeline.

By cutting out middlemen and hiring our own production staff, we’re able to complete much of the manufacturing ourselves— lowering the risk of such incidents impacting us in the future.

Since S & W’s resignation from Pawprint Press, we’ve made several improvements in our material sources and techniques which they wouldn’t have knowledge of. Rest assured, they also do not have access to any sensitive info, business, financial, or design files. Additionally these individuals have never had access to the personal information of customers or licensors.

Internal Controls

At Pawprint Press, we’re a small team and have historically operated on a high-trust basis. For convenience, all team members, including the two individuals at issue, previously had broad access to our asset repositories. We were also averse to investing time and money in internal controls, which we regarded as unfriendly and bureaucratic.

Following this incident, we have reassessed that approach and implemented stricter policies. In particular, all access by our Chinese subsidiary is now limited to a strict need-to-know, least-privilege basis.

Anti-Counterfeiting

During the production of the Axel Plush, we introduced a unique serial number with every plush, i.e. the orange tag. Scanning the QR code allows customers to verify the authenticity of their plush. This was originally created in response to cases of our designs, such as the Amicus Plush, being bootlegged.

Each orange tag is unique and can be registered to a customer’s own email address. The anti-counterfeiting feature wasn’t something we advertised publicly— because even if serial numbers are unique, bad actors might attempt to copy the physical tags. In the future we might look into upgrading these, including NFC & RFID solutions that we’re currently testing. (It’s also pretty cool tech!)

Why Still China?

Some readers might wonder: after all the challenges, the risks of IP theft, and the headaches caused by individuals mentioned in this statement, why do we continue to produce our products in China?

The politically correct answer is, of course, that these issues happen elsewhere too—and have nothing to do with the country itself. But the professional answer, and perhaps the only truly correct one, is that China remains the center of the manufacturing ecosystem for our products, if not for every product in the world.

Being the manufacturing center for over two decades, China concentrates the skilled labor and supplier networks necessary for our high-end production. Producing plushies like ours requires an extensive production chain: quality dyeing mills for custom colors, precise molding factories for metal parts, and reliable electroplating plants for beautiful finishes. Any mistake in this complex process—which we have encountered many times—can compromise the entire product.

Yes, we are aware that there are countless low-quality manufacturers in China, and we have spoken about this often. But here’s the upside: for almost every industry, there are thousands of manufacturers, and you can eventually find the ones that meet high standards.

We also have extensive networks in China, which help us reduce costs and operate at this scale. Friends and family often volunteer their expertise to support our operations. Such relationships and know-how are not easily replicable if we moved production to another country, and hiring professionals of comparable skill at market rates would be virtually impossible.

Skilled workers are also hard to find, even in China. All our craftspersons have more than 15 years of experience, a result of China’s leading role in global manufacturing over the past two decades. In more developed countries, such experienced workers have largely retired, while in less developed countries, there simply aren’t enough seasoned workers yet. We did consider moving production to South Korea, where we also have connections, but a labor market assessment quickly ruled it out.

What about the U.S.? Let’s say if you happen to have 15+ years of experience sewing delicate items and are willing to work for even high-end Chinese wages, you’re more than welcome to contact us. In the meantime, we suggest reading one of our backstage articles to see how manufacturing operates in the U.S. (at least in LA). We don’t see the point in doubling or even tripling our sales price just for a “Made in USA” label—most of the extra cost wouldn’t even go to the American workers anyway.

And don’t forget we have products other than plushes too.

We also serve a large group of international customers, who benefit from the low-cost shipping of orders directly from China. Once again, this is another advantage of China’s role in global manufacturing: with so many goods being exported, the highly developed logistics network makes shipping remarkably affordable.

Staying in China is therefore a pragmatic choice: it allows us to maintain full control over our production chain and deliver the highest-quality products at the current price point. Despite the risks, China remains the place where we can execute our work most effectively.

Thoughts

We’re in California. Before we secured our warehouse in LA, we were literally in Silicon Valley (to be precise, our office was in San Ramon but our warehouse was in Santa Clara), where “C2C” (Copy to China) happened every day — it even became an abbreviation.

Most copying is legal. The law here and in most places around the world, including China— does not recognize a proprietary right to a business idea. If you want to do something others are doing, you’re free to do it.

A key part of Silicon Valley’s success is that California largely prohibits non-compete clauses in employment: talents are free to move. That tradition stretches back a long way and was codified in Business and Professions Code §16600 as early as 1941. If you take a job to learn how someone runs a business so you can compete with them later, that’s totally allowed. You can do it right after leaving, just as TPM did.

People have built enormous fortunes copying ideas from Silicon Valley, often without paying a dime, and yet Silicon Valley remains the center of innovation. Over 150 years of limiting employment non-compete restrictions, California’s economy is now one of the world’s largest, bigger than the entirety of Japan.

Fair competition makes participants stronger.

Believe it or not, the paragraphs above were exactly what we told W at the time he left. We would never mind if it’s a fair competition.

However, we also told him that we would not sit idly by if they dared to steal. At the time, he said they would never dare to do so.

It seems they either lied or later grew bolder.

One of the most recent C2C lawsuits in Silicon Valley involves Apple suing Oppo, a Chinese smartphone company that allegedly recruited a Chinese Apple employee (who is also being sued) to deliberately collect technical information before leaving Apple and joining Oppo, enabling Oppo to develop its own smartwatch based on Apple’s trade secrets. (Those interested, and who have a PACER account, can look up case number 5:25-cv-07105 in the North District of California for details.)

Reading this news, you might think Oppo was planning to make their own smartwatch. Surprisingly, Oppo have already been producing smartwatches since 2020. Many readers of this statement may not have even heard of the brand at all.

A whole lineup of Chinese brands, including big names like Huawei, are making earbuds that look nearly identical to Apple’s. Yet, none have unseated Apple from its market position.

Nobody believes Oppo could make better watches or earbuds than Apple simply by copying Apple’s work. And it’s hard to imagine regular Apple customers even considering Oppo as an alternative. Why does Apple even bother to sue them?

Real innovation is expensive, and consumers don’t always see that. If we let people steal others’ work and ship hassle-free copies, those copycats can sell at rock-bottom prices the real innovators can’t match, because genuine creators must recoup R&D costs.

Making a successful game can be equally expensive and even more risky; selling merchandise that exploits other’s character is freeloading on their work. It is particularly infuriating to see that MiHoYo is kind-hearted enough to issue open licenses, allowing fans to create freely based on their beloved characters without legal risk, yet TPM blatantly abused this kindness. Such abuse could eventually lead to the cancellation of this rare license in the video game industry.

Sure, one might say MiHoYo is huge enough to shrug off infringement— but isn’t that the same argument some make about Apple?

If nobody stands up for justice, we’ll eventually live in a world where creativity dies and all surviving businesses are just copying each other. If the leaders in an industry ignore infringement because it’s “not worth it,” the thieves will only grow bolder, especially toward smaller businesses. To that end, we feel reassured seeing big companies using their legal tools to the fullest when it comes to protecting their intellectual properties.

Speaking of legal tools, one might be concerned that the fact the infringement occurred in China could put us at a disadvantage, as the Chinese legal system has long been notoriously unfriendly to IP infringement victims, and non-litigation remedies—such as DMCA takedowns—are also lacking. All of that is true. But one good thing about China is that a company does not need to appoint an attorney to represent it in a lawsuit—and we happen to have the best lawyer in-house. Hiring a top attorney at market rates for an international case of this complexity would be impossible for us, and honestly, you probably wouldn’t want us to spend precious money that way anyway. Luckily, we don’t have to. Let’s give credit where it’s due: Chinese law, in this instance, enables small businesses to fight for justice.

We intended to make an emotional-less, as-concise-as-possible statement, like most companies would do in such circumstances. Somehow, it turned into a long essay, especially this “Thoughts” section. For readers who have read all the way here, we’re sure you understand that it’s hard for us not to be emotional.

This is not an article asking anybody to “stand on the side of justice”. We don’t need that. We’re already handling it through litigation. Honestly, 70% of this statement is just us admitting an embarrassing fact: we spent a year building our own plush production chain and 16 months in total to produce our first fully in-house product, while TPM shipped Pink Panda just four months after their company was established.

We just hope you understand that we’re not imbeciles. Well, we might be, but the point is, they skipped the hard work.

The remaining 30% covers how they trade on other people’s popularity, including falsely claiming other people’s work as their own. It’s so lame that we’re already bored talking about it.

Every Pawprint Press product is subject to strict approval from each licensor and we need to pay royalties for the use of their rights. It has never crossed our minds to profit on other people’s intellectual properties at our own discretion, and even if it did, the first question that would come to mind is “Would people really buy it”?

Because we know more than anybody that people buy from us because they want to support the creators. That is why we dedicate maximum attention to every product, regardless of the cost. We see ourselves as a bridge connecting people’s love to those who brought the things they cherish into this world. We could never let either side down.

And we will keep doing that. We hope your support can help us continue this for as long as possible.

This, ultimately, is what this long essay is really about. We appreciate your time in reading it.

Sincerely,

Pawprint Press